“Art is either plagiarism or revolution.” – Paul Gauguin (1848-1903)

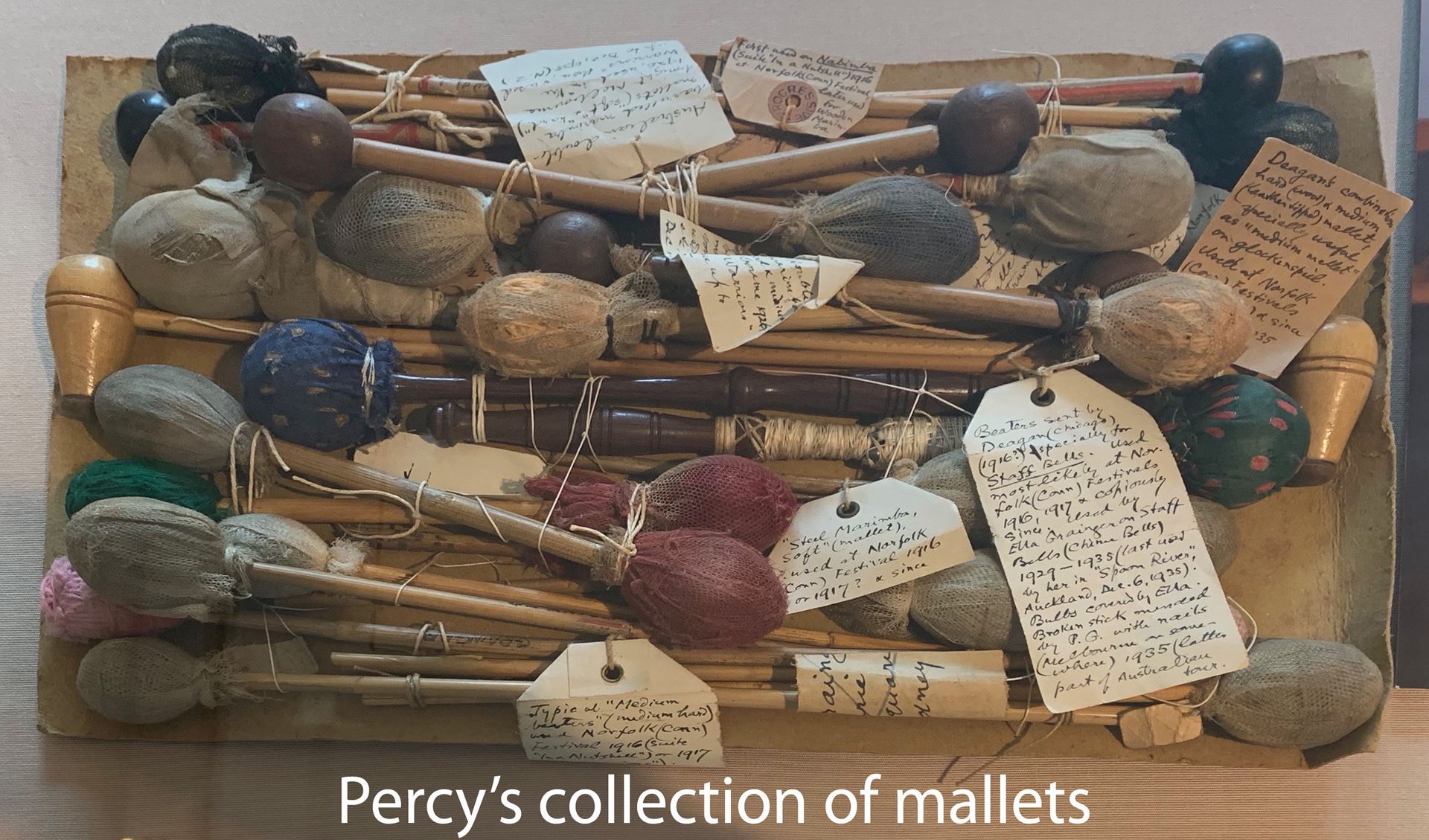

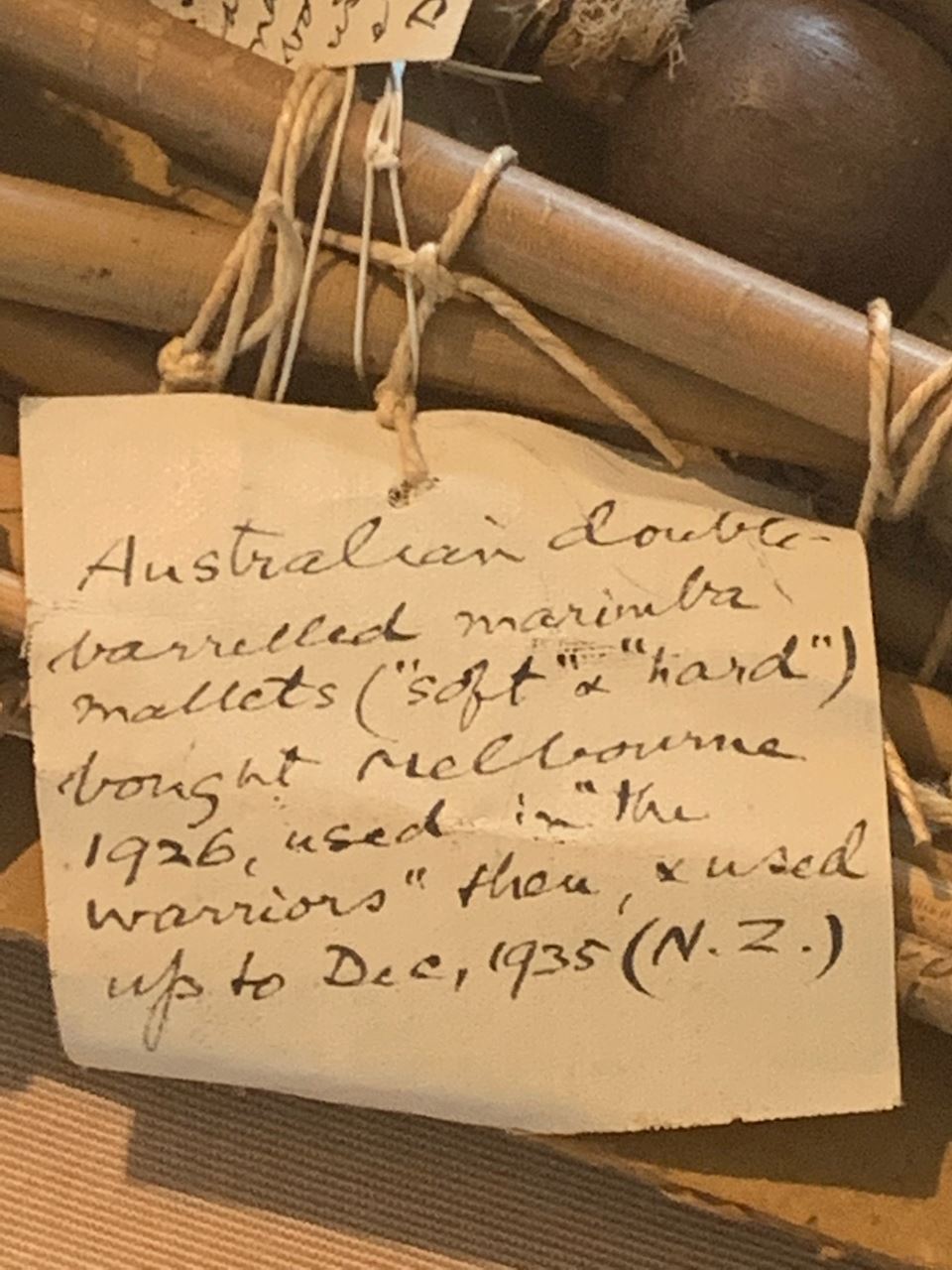

By Chalon Ragsdale. Percy Grainger’s status as an innovative genius in the area of orchestration is reinforced for me practically with each score of his I have the good fortune to study. His knowledge of the instruments is an important factor, his search for new and unique combinations of instruments is an important factor, but perhaps the most important factor in the brilliance of his orchestration is his democratic respect for each instrument’s worth and ability to contribute positively to the total fabric (Grainger might say the “weft”) of the music. Though I am constantly amazed at Grainger’s use of all the instrumental and choral resources at his disposal at any one time, as a percussionist myself, I am most keenly struck by Grainger’s brilliant use of the mallet-played percussion; what he termed the “tuneful percussion.”

Though I am constantly amazed at Grainger’s use of all the instrumental and choral resources at his disposal at any one time, as a percussionist myself, I am most keenly struck by Grainger’s brilliant use of the mallet-played percussion; what he termed the “tuneful percussion.”

Grainger’s transformational energy found fruit in a new model of orchestration in the early years of the 20th Century, as expressed most convincingly in his large orchestral works The Warriors and Suite: In a Nutshell. Grainger continued the work of Wagner and Mahler in completing the woodwind and brass families of the orchestra; but he also created a new family of instrumental color by combining the “tuneful” percussion with harp and the various keyboard actuated instruments (piano, celesta, dulcitone, etc.)

Thus, in The Warriors, Grainger provides a fourth complete family to add to the Woodwinds Brass and Strings. He used 3 players on the normal orchestral percussion - Side-drum, tambourine, cymbals, bass drum, gong, and the like. But he then added as many as eight players on Xylophone; Wooden Marimba (2 players); Glockenspiel; Steel marimba or bar-piano, or dulcitone; Staff Bells (an instrument of his own invention, consisting of up to 4 octaves of handbells strung in keyboard fashion on a wooden rack and played with various mallets); Tubular Bells; Celesta; Piano(s); and Harp.

Thus, in The Warriors, Grainger provides a fourth complete family to add to the Woodwinds Brass and Strings. He used 3 players on the normal orchestral percussion - Side-drum, tambourine, cymbals, bass drum, gong, and the like. But he then added as many as eight players on Xylophone; Wooden Marimba (2 players); Glockenspiel; Steel marimba or bar-piano, or dulcitone; Staff Bells (an instrument of his own invention, consisting of up to 4 octaves of handbells strung in keyboard fashion on a wooden rack and played with various mallets); Tubular Bells; Celesta; Piano(s); and Harp.

Though The Warriors and Suite: In a Nutshell received mixed and negative reviews (many of which seem now frankly unenlightened), the appeal of Grainger’s use of orchestration was undeniable. Writing for Musical America in August 1917, Charles L. Buchanan said,

“… Grainger’s contribution to the sheerly instrumental side of his art is obviously far and away the most important development in contemporary symphonic music. An inborn knack, a ceaseless practical intimacy with the orchestra and a utilization of a whole new army of percussion instruments […] lend his orchestra an individual timbre of an exceeding richness of texture […] and a wealth of tone color that appears to mark a new high record in the contemporary concert hall.” (Bird, p. 193; emphasis added)

Before Grainger, composers had used percussion as “salt and pepper” in their orchestral palate. But Grainger was convinced percussion could be a satisfying “course,” combining on equal footing with the other sections of the orchestra, and Warriors and In a Nutshell proved him right.

But Grainger also believed that the tuneful percussion and their cousins (piano, harmonium, celesta, etc.) could constitute a complete meal. And he proved his hypothesis with his brilliant setting for tuneful percussion (and their cousins) of Debussy’s Pagodes. Grainger realized that Debussy’s Pagodes was an attempt to render by means of the piano the sounds and textures that Debussy had been exposed to at the Javanese exhibit at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle (International Exposition).

In 1934, Grainger published a series of twelve lectures under the collective title A Commonsense View of All Music. In the eleventh lecture, “Tuneful Percussion,” Grainger wrote,

“Of late years the bell-makers of Europe and America have adapted many Asiatic and other exotic tuneful percussion instruments to our European pitch and scale requirements, with the result that we are able to decipher Oriental music from gramophone records and perform then on the Europeanized Oriental instruments whenever we want to.

I have tried the experiment of orchestrating Debussy’s Pagodes for a complete tuneful percussion group - thus, as it were, turning back to its Oriental beginnings the Asiatic music Debussy transcribed for a Western instrument (the piano). In so doing I am merely giving it back to the sound-type from which it originally emerged.”

Most sources point to Edgar Varese’s Ionisation (1929-1931; first performed 1933) as the first percussion ensemble. Might not Grainger’s setting of Pagodes (1928) be worth considering, at least as “among the first?”

One of the earliest anthologies of writings by and about Grainger was A Musical Genius from Australia, published by the University of Western Australia Department of Music, compiled and with Commentary by Teresa Balough. The word “genius” has an elusive definition. Does “genius” describe a person? Or is it a quality all of us can possess in some measure? If it is a quality, perhaps it is the ability of a singular individual to look at what the rest of us are looking at, but see something different. If we accept that definition, then Percy Grainger certainly had a quality of genius, of seeing things the rest of us missed, and the “tuneful percussion,” and the world of percussion in general, are the beneficiaries of that genius.

One of the earliest anthologies of writings by and about Grainger was A Musical Genius from Australia, published by the University of Western Australia Department of Music, compiled and with Commentary by Teresa Balough. The word “genius” has an elusive definition. Does “genius” describe a person? Or is it a quality all of us can possess in some measure? If it is a quality, perhaps it is the ability of a singular individual to look at what the rest of us are looking at, but see something different. If we accept that definition, then Percy Grainger certainly had a quality of genius, of seeing things the rest of us missed, and the “tuneful percussion,” and the world of percussion in general, are the beneficiaries of that genius.

Click here to view a sample of Grainger's manuscript score for his setting of Debussy’s Pagodes.

Click here to view printed full score of Grainger's setting of Debussy's Pagodes as published by Bardic Edition (score and performing material available on rental from Schott Music).

To hear a recording of Percy Grainger’s setting of Debussy’s Pagodes.

https://www.google.com/search?q=Pagodes+Rattle&rlz=1C5MACD_enUS545US546&oq=Pagodes+Rattle&aqs=chrome..69i57j33i160.2623j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

To see a performance of “Arrival Platform Humlet,” the opening movement of Suite: In a Nutshell, conducted and with commentary by Michael Tilson-Thomas. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W2gMjtlYthk

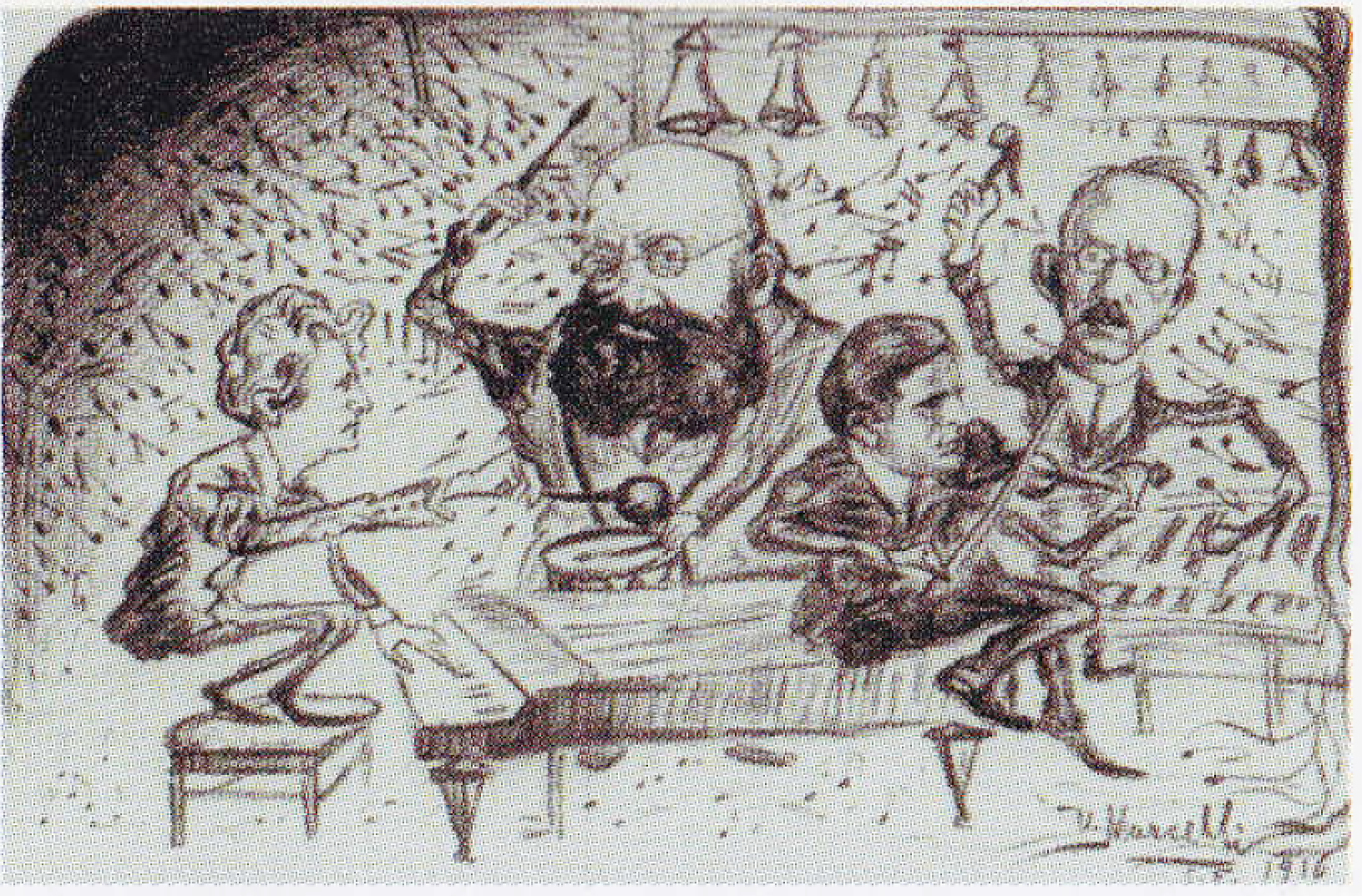

Ugo Marcelli’s 1916 caricature of Grainger’s suite In a Nutshell for tuneful percussion and orchestra, featuring (from left to right) Percy Grainger, Aldred Hertz (conductor of the San Francisco S.O.), Louis Persinger (concertmaster) and Redfern Mason, the music critic for the San Francisco Examiner.