Paul Jackson. Honorary Visiting Senior Fellow, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK, and International Percy Grainger Society Board Member.

‘There is one thing I look down on new-timey folk for: their not being able to write A LONG LETTER.’1 So wrote Percy Grainger to his friend and fellow-musician Gustav Adolph Nelson in the summer of 1942. Among his many accomplishments – composer, pianist, conductor, writer, teacher, folk-music collector, artist, inventor – Grainger’s ability to write letters, often long letters, remains a relatively unexplored part of his life’s work. Ranging from the conversational and practical, to the ideological and autobiographical, Grainger’s letters form perhaps the largest part of his output – estimates range between 10,000-50,000 letters – and chronicle his personal and artistic life from his early years in Australia, through his formative studies in Germany from 1895-1901 and his maturation in Edwardian English concert society between 1901-1914, to his long life in America, his adopted home, from 1914 until his death in 1961. Grainger’s fame, firstly as an international concert pianist and then as a composer, opened the doors to acquaintances with composers, musicians, artists, poets, writers, folklorists, educators, society figures, royalty and even an American president. His letters detail his professional and personal activities, plotting the arc of his career, and also serve to chart the course of the development of his views on music, the creative artist, race, sex and language (among many other things). From the exuberance of his early writings, which burst forth with accounts of his voracious engagement with the world and his seminal encounters with a range of influences, through the mid years of detailed, perhaps even obsessive, self-documentation, to his old age, when an emotionally mellower Grainger enjoyed new-found recognition, the letters provide an essential insight to a thinker of distinction.

‘There is one thing I look down on new-timey folk for: their not being able to write A LONG LETTER.’1 So wrote Percy Grainger to his friend and fellow-musician Gustav Adolph Nelson in the summer of 1942. Among his many accomplishments – composer, pianist, conductor, writer, teacher, folk-music collector, artist, inventor – Grainger’s ability to write letters, often long letters, remains a relatively unexplored part of his life’s work. Ranging from the conversational and practical, to the ideological and autobiographical, Grainger’s letters form perhaps the largest part of his output – estimates range between 10,000-50,000 letters – and chronicle his personal and artistic life from his early years in Australia, through his formative studies in Germany from 1895-1901 and his maturation in Edwardian English concert society between 1901-1914, to his long life in America, his adopted home, from 1914 until his death in 1961. Grainger’s fame, firstly as an international concert pianist and then as a composer, opened the doors to acquaintances with composers, musicians, artists, poets, writers, folklorists, educators, society figures, royalty and even an American president. His letters detail his professional and personal activities, plotting the arc of his career, and also serve to chart the course of the development of his views on music, the creative artist, race, sex and language (among many other things). From the exuberance of his early writings, which burst forth with accounts of his voracious engagement with the world and his seminal encounters with a range of influences, through the mid years of detailed, perhaps even obsessive, self-documentation, to his old age, when an emotionally mellower Grainger enjoyed new-found recognition, the letters provide an essential insight to a thinker of distinction.

To date, only three volumes of letters have been published: The Farthest North of Humanness: Letters of Percy Grainger 1901-14 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1985), the first and most significant presentation of Grainger’s letters from his years in London; The All-Round Man: Selected Letters of Percy Grainger, 1914-1961 (Oxford University Press, 1994), 76 letters from a wide range of areas following the composer’s move to America; and Comrades in Art: The Correspondence of Ronald Stevenson and Percy Grainger, 1957-61 (Toccata Press, 2010), correspondence between Grainger and the Scottish pianist and composer, Ronald Stevenson, covering the last four years of Grainger’s life.

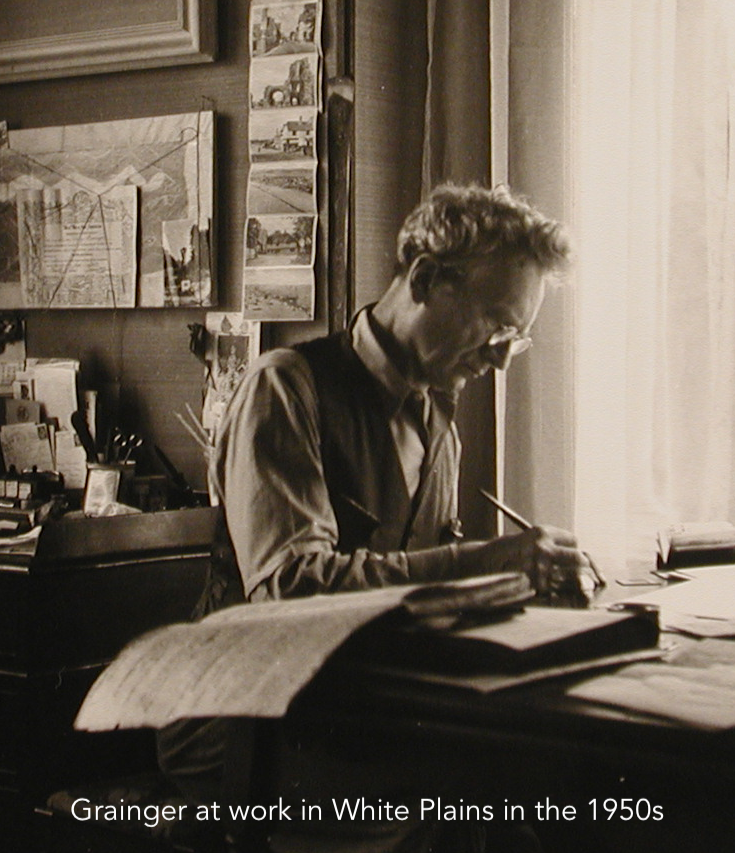

Central to Grainger’s body of writing is the group of 33 letters2 known as the ‘Round Letters’. Intended for posterity (as, indeed, was all of his output), these letters were copied and sent to fellow composers, friends, family and acquaintances periodically from 1942 until 1958, three years before his death. Grainger frequently wrote letters and articles whilst travelling by train or boat between concert engagements, often on headed hotel notepaper. As he took no other form of transport (he would not fly), such travelling could take several hours or, in the case of overseas trips, several weeks or months. Grainger used his time fruitfully on these trips, composing, attending to his business affairs, writing to friends, family and professional colleagues, and writing articles. He would generally write by hand, and then type up the draft, making several copies with his own, in-house, copying systems at White Plains. Grainger’s efforts to establish the Grainger Museum in 1938 as a study centre for Australian music meant that he not only lodged many of his letters there – a boon to modern researchers – but also asked letter recipients to send him back letters for which he had no copies (such requests were not always met with approval, particularly from ex-lovers!).

Central to Grainger’s body of writing is the group of 33 letters2 known as the ‘Round Letters’. Intended for posterity (as, indeed, was all of his output), these letters were copied and sent to fellow composers, friends, family and acquaintances periodically from 1942 until 1958, three years before his death. Grainger frequently wrote letters and articles whilst travelling by train or boat between concert engagements, often on headed hotel notepaper. As he took no other form of transport (he would not fly), such travelling could take several hours or, in the case of overseas trips, several weeks or months. Grainger used his time fruitfully on these trips, composing, attending to his business affairs, writing to friends, family and professional colleagues, and writing articles. He would generally write by hand, and then type up the draft, making several copies with his own, in-house, copying systems at White Plains. Grainger’s efforts to establish the Grainger Museum in 1938 as a study centre for Australian music meant that he not only lodged many of his letters there – a boon to modern researchers – but also asked letter recipients to send him back letters for which he had no copies (such requests were not always met with approval, particularly from ex-lovers!).

The Round Letters are also distinguished by their use of ‘Blue-Eyed English’ (also known as ‘Nordic English’ or ‘Rosy-Race-y English’), Grainger’s attempt to formulate a language which replaced words he thought of as having Latin and Greek roots with words of his own devising based on Anglo-Saxon terminology. The preface to The Love-Life of Helen and Paris, written in 1924 when he and his future wife Ella Ström were courting, sums up his thoughts on the matter:

The English stretches of this story are written (as well as I can) in “Nordic English”. I have always believed in the wish-for-ableness ((desirability)) of building up a mainly Anglo-saxon-Scandinavian kind of English in which all but the most un-do-withoutable ((indispensible)) of the French-begotten, Latin-begotten & Greek-begotten words should be side-stepped ((avoided)) & in which the bulk of the put-together ((compound)) words should be willfully & owned-up-to-ly ((admittedly)) hot-home-grown out of Nordic word-seeds. My nature-urge ((instinct)) tells me that speech (like tone-art ((music)) & all other arts) ought to be over-weighingly ((preponderantly)) a forth-showing ((manifestation)) of race, place & type, & that nothing is gained (at least from an artist’s mind-slant ((attitude))) by making speech a gathered-togetherness ((conglomeration)) of worn-out Europe-wide word-chains ((sentences)) such as “in commemoration of this illustrious anniversary”, “this involved situation demanded a readjustment of the entire machinery of representation”, & the like.

Such language not only reveals something of Grainger’s character – not least, his preoccupation with notions of race – but also frequently make for patterns of expression that capture particular ideas in a revealing way. Commenting on the Declaration by United Nations in 1942, Grainger writes that:

‘First of all, world-haps: I have always preached that world-peace (the one thing we all yearn for, of course) could only be brought about by team-work between the British World-Realm ((Empire)), America, Russia & China. And now this team-play (almost unthinkable tho it seemed only a short while ago) is fact-fully ((actually)) happening. I have always said that the mete-ment ((measurement)) of any theed’s ((nation’s)) clear-thinkingness is its understanding of the Russian out-try-th ((experiment)). I have always longed to see the whole English-speaking world at-oned. I have always longed to see the whole Rosy-Race-y ((Nordic)) world brought together in spirit. Now all these hopes are fulfilled. So I feel more at rest than I have for many years. [Feb 15-17, 1942].

Grainger’s hectic concert life is chronicled in some detail throughout the letters. Even in his sixties and seventies he toured throughout the US, performing at civic halls and high schools. His music enjoyed something of a renaissance during these years, and the frequent performances he took part in or attended gave him the opportunity to reflect on a lifetime of composing:

I think I wrote you in my last Round Letter that this season was proving a somewhat dull one for me, from my tone-wright’s ((composer’s)) angle. This dullness has somewhat lifted, toward the end of the season. The other day in Boston I heard Green Bushes & To a Nordic Princess very finely given – & I think highly of the last-named piece, as being truly string-&-wind-band ((orchestra))-minded. Ella & I have just come from Oberlin College, Ohio, where I gave Hillsong II (22 single winds), a stunningly played & sung group of English Gothic Music (13th to 17th year-hundreds), my seldom-done County Derry Air (which is the setting of Irish Tune from Co. Derry written in 1920 for sing-band ((chorus)), organ & band—a setting which has nothing in common with the 1902 setting. The 1920 setting has a Handel-like bredth & grandness about it) … So I have nothing to grumble about, just now, on the ground of non-forth-played-ness ((non-performance)). To hear Hillsong II (first scoring, 1907) is enough to at-rest-set me for some time. [May 17, 1944].

Whilst an uncharacteristically humorous Percy noted in 1958, after hearing a performance of the piano-only version of Random Round, that:

At Cincinnati I heard for the first time a properly worked out perform[ance] of my Random Round in the dish-up for 6 pianists at 2 pianos (the original form is 3 voices, 3 strings, 2 guitars, flute, xylophone, wooden Marimba, ukulele etc): 6 elderly ladies, all with immense backsides, romped away at terrific speed & quite note-perfect. The sound is utterly unlike anything else. [March 25, 1958] 3

On a more serious note, Grainger frequently makes the case that the creative artist’s works should be judged in the light of a full understanding of their whole life, that youthful output is every bit as valid as mature work, and that we hear music in the light of previous experience and earlier knowledge:

In dealing with an oversoul [genius] 4 we must, I feel, sense the truth of Goethe’s saw “Art is who-th” ((personality)). We listen to Meistersinger without forgetting that Wagner before it wrote the Ring & Tristan. If Wagner had done away with all his earlier works before writing Parsifal, we would listen to Parsifal in a poorer mood. When we listen to the Minuet of a Symphony we are still somewhat swayed by the soldierliness of the first movement; as we listen to the bustle of the last movement, we are still somewhat under the spell of the slow movement’s dream-world. Art cannot be sundered from its hap-lore ((history)) any more than can a tree from its roots. And the greater the oversoul, the truer this is of his art; for we judge him by his whole art-life & by the breadth of his lifelong intake. [May 17, 1944].

The Round Letters – all 85,000 words of them – are currently being edited and prepared for publication. To date, only 4 Round Letters have been published in full, in The All Round Man (Oxford University Press, 1994) and Grainger on Music (Oxford University Press, 1999) and publication of the full set of letters will provide another useful resource to researchers and to the general public who want to better understand the thoughts behind Grainger’s ever-fascinating, and sometimes perplexing, music!

1 Letter dated 11 June 1942 from Grainger to Gustav Adolph Nelson (1900-1979), pianist, organist and conductor, and music director of the Gustavus Choir at Gustavus Adolphus College, Saint Peter, Minnesota from 1930-45.

2 The Granger Museum’s (incomplete) collection of Round Letters suggests there are 39 letters in the collection. However, my research has shown that the first six letters in the collection, dated between 1924 and 1940, are not part of the Round Letters proper, which Grainger identifies as beginning on 15 Feb, 1942 in his own cataloguing system.

3 Concert given on 11 March 1958 at the Wilson Auditorium, University of Cincinnati, with Grainger’s former pupil, Dorothy Stolzenbach Payne, and members of The Keyboard Club. The ‘6 elderly ladies’ were identified as Mrs. Robert Pugh, Mrs. Elmer Hess, Mrs. Ranald West, Mrs. Ford Larrabee, Mrs. Luke Jacobs and Mrs. Raymond P. Myers.

4 ‘Oversoul’ is generally translated as ‘genius’, although the latter term is neither as poetic, not perhaps as nuanced, as the former.