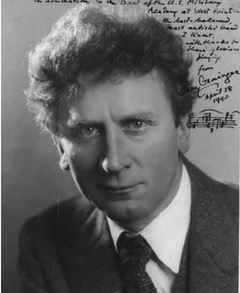

This led composers to start writing for what is now call ‘Flex-Bands’ or ‘Flex-Ensembles.’ The interesting thing is a prominent, 20th century composer, Percy Grainger, had already employed this technique over 100 years ago – Elastic Scoring is what he called it. This was all part of Grainger’s philosophy of Democracy in Music. Providing music in such a manner that all different types of ensembles from a few players to 100s could perform the same work with success. What better way to tell the story than through Grainger’s own words:

My “elastic scoring” grows naturally out of two roots:

1. That my music tells its story mainly by means of intervals and the liveliness of the part-writing, rather than by means of tone-color, and is therefore well fitted to be played by almost any small, large or medium-sized combination of instruments, provided a proper balance of tone is kept.

2. That I wish to play my part in the radical experimentation with orchestral and chamber-music blends that seems bound to happen as a result of the ever wider spreading democratization of all forms of music.

As long as a really satisfactory balance of tone is preserved (so that the voices that make up the musical texture are clearly heard, one against the other, in the intended proportions) I do not care whether one of my “elastically scored” pieces is played by 4 or 40 or 400 players, or any number in between; whether trumpet parts are played on trumpets or soprano saxophones, French horn parts played on French horns or E flat altos or alto saxophones, trombone parts played on trombones or tenor saxophones or C Melody saxophones; whether string parts are played by the instrument prescribed or by mandolins, mandolas, ukuleles, guitars, banjos, balalaikas, etc.; whether harmonium parts are played on harmoniums (reed-organs) or pipe-organs; whether wood-wind instruments take part or whether a harmonium (reed-organ) or 2nd piano part is substituted for them. I do not even care whether the players are skillful or unskillful, as long as they play well enough to sound the right intervals and keep the afore-said tonal balance – and as long as they play badly enough to still enjoy playing (“Where no pleasure is, there is no profit taken” – Shakespeare).

This “elastic scoring” is naturally fitted to musical conditions in small and out-of-the-way communities and to the needs of amateur orchestras and school, high school, college and music school orchestras everywhere, in that it can accommodate almost any combination of players on almost any instruments. It is intended to encourage music-loves of all kinds to play together in groups, large or small, and to promote a more hospitable attitude towards inexperienced music-makers. It is intended to play its part in weaning music students away from too much useless, goalless, soulless, selfish, inartistic soloistic technical study, intended to coax them into happier, richer musical fields – for music should be essentially an art of self-forgetful, soul-expanding communistic cooperation in harmony and many-voicedness. (1)

Elastic Scoring was a natural result of Grainger’s life-long philosophy of Democracy in Music (1931)

of Democracy in Music (1931)

“A chance for all to shine in a starry whole.’ Some such thought as this underlies, I suppose, our working conception of democracy. Democracy seems to our mind’s eye not merely a comfortable system of ensuring personal independence & safety to each man, but also an adventure in which the oneness & harmonious togetherness of all human souls is lovingly celebrated – for it is obvious that democracies are just as patriotic & humanitarian as they are freedom-loving.”

“Such a banner seems fair enough for any upward-yearning soul. And, in fact, this ideal, as applied to life, art & thought, has spurred on many a genius, such as Walt Whitman, Tennyson, Martin Luther, Bach, Grieg, Edgar Lee Masters, etc.”

“Yet, in spite of the master-minds that have championed democracy, & in spite of the fact that the measure of a country’s democraticness is almost exactly the measure of its prominence in freedom, science, power & prosperity, we hardly ever meet an individual (even in those lands most nearly democratic)who whole-heartedly believes in the practical wisdom of democracy; nearly always the individual is held back from a happy embrace of democratic doctrine by the sway exerted over his nature by old-time influences that make for superstition, personal greed, leisure-worship, celebrity-hunting, slavishness & lack of selfhood. As a result, so many of those who would give lip-service to democracy where the large issues of world affairs are at stake are unwilling to practice democracy in the small & immediate affairs of their everyday life. As a result of this weakness & blindness in so many individuals we may truly say that democracy (like Christianity, like socialism like many another noble idea) has never yet been given ‘a fair chance.’ Yet its cause goes marching on.”

“It is not the same as the cause of the best, the deepest, the grandest, the loveliest art music? Its cause, also, goes marching on with quiet but steady invincibility, although retarded by the blindness & smallmindedness of some many individuals – amongst whom, it always seems to me, there is too large a percentage of highly-trained professional musicians. These individuals seem to forget that art music is an essentially democratic art, an art that mingles souls while it mingles sounds, an art in its self-forgetful collectivism transcends individualism, an art of fusion and cooperation, an art that feeds on soul-ecstasy but starves on mere cerebral cleverness. In the highest forms of art music, as in democracy, ‘the starry whole’ (the radiant glory of art itself, of collective humanity itself) counts for at least as much as ‘the chance for all to shine.’ Technically, this means that the various melodic lines, that make up the harmonic texture, must enjoy, at various moments, equal opportunities to be independent, prominent & volitional; but that the splendor & beauty of the composite whole is the goal that none may lose from mind.” (2)